... by Ian Brooks

No Triumph No Tragedy

We've run the Berkeley event three times now, and it's been pretty successful. This year was more, shall we say, eventful... than successful. We learn something every year, and this year there were some hard lessons.

We kicked the event off an hour late, mainly due to the visibility which was down. When we finally started, at 12:00, things were looking OK. It was a bit windy, but not too bad. What we had not noticed was just how fast the wind was picking up.

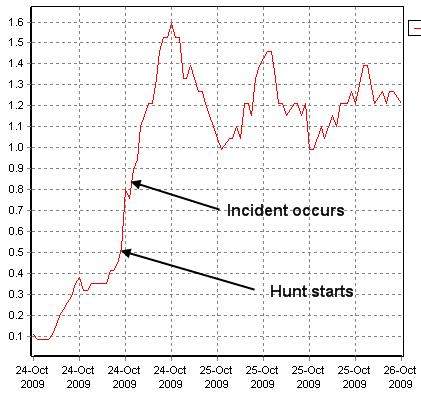

Wave height at Hinkley Point - 40 miles away, but an indicator of how fast the weather was changing that day

Wave height at Hinkley Point - 40 miles away, but an indicator of how fast the weather was changing that dayAs ever, the briefing was very particular on one point - that each pilot must be sure that their craft was up to the conditions, and that their own skills were up the craft. Will your craft get you back? Will you get the craft back? The decision to operate involves acceptance of personal risk... also for the organisers.

Meanwhile, the wind was picking up...Our first breakdown occurred in minutes - the Deacons BBV misfired its way back to within 400 yds of the slip before finally conking out. After 10 minutes of watching them drifting out on the tide, we decided to go fetch them in, and I was dispatched to towing duties - which was uneventful.

The wind was picking up...After about 45 minutes of hunt time, one or two people had wisely decided to retire, and we decided that the conditions were becoming too difficult to guarantee recovering any pilots & passengers from broken-down craft, so that meant we had a key plank of the risk assessment out of action. We had to halt the event.

Then came the task of bringing everyone back. As we had no means to contact individual pilots, we took stock of who was where, and when they were expected back. As usual, Heather and the team in Control were on top of these details, and gave a comprehensive report of people, locations and times. All were safe, although we had two breakdowns reported.

And the wind continued to pick up...A few stragglers returned, and we then had two remaining teams out, both with breakdowns, one at Sharpness and one further upriver. Bryan and I set out to assist. Locating Peter, who had set off back leaving his Dad with the breakdown, I escorted him back. Nearing Sharpness, however, his craft also misfired and was beached at Sharpness with the others... I returned to Control to fetch a fresh battery.

And the wind picked up...On returning round the harbour gates, the Sev was broached by the tailwind, lost thrust & steering, and during an attempt at corrective manoeuvres - she went over. Just like that. No warning, just "Superman" into the dark brown morass that is the Severn.

The next few seconds were those extra-long ones you get in times of extreme stress... no panic, but a series of thoughts occurred to me as I floated, without knowing which way was up or down, wide-eyed in the brownness.

"I'm in"

<splash>

"I'm going to come up under the craft"

<kick-kick>

"Shouldn't this lifejacket have gone off?"

<woooossshhhh>

Then I popped up like a cork. Locating the upturned hull, I was able to climb on. Wet, but safe. And then it was a waiting game.

From the bank, all that could be seen of this event was the craft disappearing instantly from view. This must have been quite a shock... particularly as I surfaced on the blind side of the hull, and could not be seen. The Coastguard were called, and rescue services set into action. I later learned that a Helicopter was scrambled, although it was stood down before reaching the scene once it was reported that I was safe.

Once on the hull, I knew I was pretty safe and could be thankful for three things:

- The lifejacket. Bear in mind that my immersion suit contains 70N of buoyancy, but it do not bring me up, and with the disorientation I did not know which way to swim. It was only the lifejacket that overcame the heavy winter gear I was wearing, without it I could easily have drowned. Best 70 quid I ever spent!

- The immersion suit. The suits that most people are wearing these days are literally a life saver. They do contain some buoyancy, but more importantly they will protect you from hypothermia for up to an hour in cold water. Go into the Severn in March without one, and you may die from cold in 10 to 20 minutes! In October, with the water still warm from the Summer, it's not so bad, but still I was glad of the suit to protect me from the icy wind.

- The crafts inherent buoyancy: The Sev turned turtle, but she includes more than 200% buoyancy within the structure and in two buoyancy tanks. It floated high, level and stable and provided a safe refuge. I could have waited there for hours if necessary.

Getting onto the hull was not entirely straightforward though - it's completely smooth, with no handholds and many gallons or seawater trapped in my clothing weighed against my efforts! Again, the design of the suit was working for me... it has drain vents all over the place, pockets, cuffs, and as I grabbed a handful of skirt and pulled, it drained, and I was able to slither up.

Now my thought turned to rescue. The phone was fried. The radio was two feet underwater. With the flares. Oh bugger...

On this occasion, all was OK, I saw rescue on the way - Bryan and Nelson, what better crew could you want when the chips are down? No faffing, and an instant understanding of what was needed. I managed to locate the towrope on the Sev. Another lesson - it was exactly where I left it, and pre-attached. I had to grope under the water (carefully!) but it was there and not snagged.

Throwing a rope is a simple skill - but one that shouldn't be learnt during a rescue!. I spent a hour in the garden some years ago to practise. Thankfully. How many times have you seen a bird-nest cast 6 feet, stop, and fall into the sea? It takes about a minute or so to prepare the rope. Carefully coil it over the left hand, making sure that coils do not overlap. Then take half the coils into the right hand, and holding the left hand extended in the direction of throw, cast the right hand underarm. This sent a healthy amount of rope safely over Bryans bows, and once a connection was established, he was able to tow the whole rig back to shore. At that, I escaped up the rope to find a warm camper and gratefully received a spare set of clothes - which mostly fitted! Cheers Conrad!

After a hot mug of tea, I was back in the game and the recovery of the craft from the mud was the next priority. Fortunately, with the help of Conrad (and a spare sparkplug that Ivor just happened to have in his pocket), we got the lift engine to run and extricated the craft. Right now it's sitting forlornly on the drive, the engines are in the garage in intensive care. The lift engine, which was a bit jiggered anyway, is going to be scrapped, but the thrust engine is coming clean now.

The amount of damage done by the water is unbelievable. After a few days, electrical contacts were already beginning to corrode, and it's clear that the electrics will have to be stripped out and replaced to assure future reliability. The engine oil is finally coming clean, but I had to strip the starter, carbs and all ancillaries, and all the wiring is cut off for replacement. And what exactly do you do with three gallons of mixed petrol and muddy water?

Happily, the only loss this time was money and a certain amount of embarrassment. Even the Coastguard commented that we had the right equipment and our organisation was good, and Harbourmaster sent me a nice note too, so our reputation appears intact.

Having said that, we all learnt lessons that day. After talking to Bryan and the farmer, it seems like there will be another Hunt next year, but with certain changes to reduce the chance of anything like this happening again.

The Surveyor in happier times...

The Surveyor in happier times...Firstly, we will ask that all pilots remain in contact with Control even when underway. This isn't expensive, all that is needed is a hand-held radio connected to a cheap ear-piece worn under the ear defender. Then we can broadcast a recall to everyone should there be a need, or locate individuals. A suitable radio is about £40-50 from ebay - what price safety? With this radio worn in the pocket, that covers the "oh bugger" moment nicely too, you could make your mayday call from the water, and the rescue services can direction-find on your signal, to home in on you should they need to.

Secondly - we need a more objective measure of conditions and to pre-set limits. We will use an instrument to ensure wind remains in a reasonable range - but, as always the decision to operate will remain with the Pilot, and the organisers will not make any specific recommendations regarding whether conditions are safe for any particular craft or pilot. We will, as before, halt the event if some part of the organisation is put at risk.

Personally, I would advise all persons on the Severn to use a proper 150N lifejacket - these start at about £40 for a manual one, although I would advise automatic for a few pounds more. A 50N buoyancy aid is just not enough - you will sink. Seriously! I was that man...

And so, what caused the craft to go over? The short answer is the wind, funnelled around the docks at Sharpness, was making gust up to 45 or 50 MPH, as measured at the Coastguard's office.

The craft would have survived this without a range of other factors which caused it to broach sideways-on to the wind. Not least of these was the "human factor" -

I made a critical mistake in reducing the lift engine RPM immediately before the incident - a decision that was made due to the lack of proper fairings to keep the spray off the drive belts, resulting in loss of thrust and steering. I knew that reducing lift would reduce the spray, restoring thrust and steering, which should have allowed me to regain control, had the wind not intervened. There will be some changes to the craft for next year to prevent the loss of thrust, which will allow me to maintain control and prevent similar incidents in future.

So there you go - it was my own fault. Following a long, hard look into the circumstances, I can say that I put the craft into an unsurvivable position and then it was overwhelmed by the wind and sea. I'm just able to be thankful for having invested in good equipment that did not let me down when things went bad.

So it's thanks to everyone who helped to make a bad situation better, from those who called 999, Bryan and Nelson for attending the rescue, Louise and Conrad for providing dry clothes & hot tea, and all who helped to recover the craft. Thanks to everyone, I was very grateful.

The other rescue

The other rescue